THE EMBRACE OF THE INTERIOR

In appreciation of the dedicated members of the MSF movement worldwide.

At the frontier, the transition is sudden. Gone are the evenly paved roads and ordered countryside of northwestern Rwanda. The senses assaulted immediately by the hurly burly that is eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) today. I was entering the DRC via Goma, provincial capital of North Kivu and chronic poster city for refugees. Since the displacement of the Hutu v. Tutsi conflict from Rwanda into bordering states in 1994, Goma has served as bellwether and emblem for the developed world’s humanitarian response to one of the major conflicts of our time.

My ultimate destination was Rutshuru, a small town 90 kilometers north of Goma. The road north, challenged by the rugged volcanic highland geology and equally marred by the 2002 Nyiragongo eruption and evident neglect, skirts several sections of the majestic but heavily mined Virunga National Park. Hardened genocidiares of several rebel armies (CNDP and FDLR), the ragtag soldiers of the National Army (FARDC) and the UN blue helmeted (and turbaned) MONUC force are currently in a tense regional stand-off which overwhelms the shattered local village populations as well as the endangered resources of arguably the planet’s most spectacular national park.

Although currently benefitting from a lull in actual combat, L’Hopital General Referent-Rutshuru pulsed with a steady rhythm as it tended to the health requirements of a traumatized and vulnerable populace. Negotiations between Medecins sans Frontieres (MSF) and the Congolese Ministry of Health resulted in a memorandum of understanding (MOU) giving MSF significant control and financial responsibility for operation of the hospital. Since 2005, the French “section” of MSF has hired and paid the salaries off hundreds of local staff selected via a rigorous interview process. The aid group’s intricate international administrative web laboriously recruits and transports a constantly rotating equipe of 18 expatriates to operate the hospital. Terms of the MOU include provision of those critical needs that MSF has become renowned in meeting: clean water, regular electricity, essential medicines, supplies, transport and communications. The operation of HGR-R is a major tour de force propelled by an annual budget of nearly 5 million Euros plus funds from Congo’s Ministry of Health.

The organization’s Human Resources department is tasked with providing adequate staffing for maintenance of a 24/7 surgical service. Current volume warranted three surgeons: one Congolese, two expatriates. I was arriving for the “typical” surgical tour of duty: four weeks; replacing another experienced North American surgeon and MSF recidivist, Mary Ann of New York City. As she’d departed several days before my arrival and with Claude, the Congolese surgeon, still in Haiti for intensive orthopedic training, my new colleagues, Maire and Muthu, were intensely relieved to witness my on-time arrival in reasonable health. Muthu a young surgeon from southern India with a pragmatic and efficient manner briefed me on schedules, several difficult cases and general logistics over lunch shortly after my arrival. Aware of some foreshadowing, I wasn’t surprised by the mid-meal phone call summoning the two of us immediately to the hospital for a patient with a “surgical abdomen”.

Four previous surgical missions in Africa with MSF had prepared me for the inevitability of performing an emergency surgery within hours of arriving on site. I knew instantly the month would be far busier surgically than any I’d experienced in recent memory. The experience would push me to my physical limits with much energy being devoted to self-preservation and staying well. Buoyed by a rich pranic breath, I resolved to live each day in the moment and resist urges to begin a countdown.

The bloc operatoire at HGR-Rutshuru is one of the larger jewels in MSF-F’s surgical crown. With five years of constant striving, millions of Euros of financial support and the development of (and adherence to) protocols, the humble two room “theatre” achieves 500-800 operative interventions a month. It manages a respectable morbidity and mortality rate in a region that manifests few other examples of successful ventures. It was thrilling to encounter clean and well-maintained instruments, good lighting and a motivated and well trained OR staff. I was relieved to have the support and camaraderie of enthusiastic surgical colleagues as many smaller missions utilize a single surgeon.

Muthu and I encountered a typical typhoid intestinal perforation as we entered our obese middle-aged patient’s abdomen after completing the six km ride back to the hospital. The potentially lethal problem was a single 3-millimeter rupture of the distal small intestine, the ileum, near its junction with the colon. We confidently explored for other pathologies, irrigated with gallons of fluid, set about freshening up the margins of the perforation and finished by performing a standard two-layer repair. Within little more than an hour, we’d resumed the day’s programme of scheduled interventions-usually 15-20 cases. These operations involved setting fractures, debriding burn wounds and draining abscesses.

Our typhoid patient, whom we expected would be cured and heading home within a week, had further lessons in surgery in Africa for us. She experienced what the trade refers to as a “stormy post-operative course” and ultimately died an anguished death twelve days later. Two days following surgery, she developed a generalized, painful swelling of her left leg and some breathing difficulties. Western imaging studies were not possible but pulse oximetry, a high-tech yet affordable tool in resource scarce settings, showed a desaturation of oxygen in the blood. The patient was placed on blood thinners to break-up a suspected blood clot in the lungs yet she continued to struggle. Additional antibiotics were administered but failed to prevent purulent fluid appearing in the abdominal wound.

As we commenced her second laparotomy some six days after the first, Muthu and I suspected our intestinal repair had failed. We blamed ourselves for not performing a more “conservative” surgery the first time around. Upon opening we found our repair intact but were stunned to see six new intestinal perforations clustered near the same area. Two feet of small intestine were then removed and fecal flow diverted with creation of an ileostomy to the abdominal wall. Aggressive care in the ICU followed but renal failure and pelvic abscesses developed. A third laparotomy ensued but proved too much for the patient and she expired in the recovery room never having regained consciousness. This initial case and other surgery related mortalities to come offered a sober reminder that there was still much to learn about the provision of safe, effective surgical care in hostile environments.

Bed counts for many rural African hospitals are shifting targets. Often beds have several occupants; many patients don’t yet have a bed, making do in various nooks and the hospitals’ carpentry shops routinely construct more bed frames when need arises. HGR-R held 250-300 hospitalized patients, all carefully triaged to only those with “urgent” conditions. The facility is a relic from the colonial age, a series of long low-slung buildings connected by deeply guttered sidewalks underfoot and metal awnings overhead. Each building houses a specific service. Internal Medicine, Pediatrics, Maternity and Surgery 1 & 2 were typical services: two long rows of beds facing each other with little in the way of privacy screens. Minimal effort is made to segregate sexes, ages and even conditions given the high volume and rapid turnover. It is known that quality of care improves with concentration of specific treatment regimens so specialized units have been created for Burns, Intensive Care, Neonatology, Orthopedics and Post-Caesarian care. The intensifying utilization of sexual violence as a tool of ethno-tribal warfare and terrorism, having reached a shocking apogee in the DRC, requires a separate service for VVS (Victimes de Violence Sexuelle) patients. Here known as Village des Mamans.

The surgeons are responsible for four buildings: Surgery 1 and 2, Burns and Orthopedics. Our patient load seems to be about 120. We are able to see all these patients only twice weekly; a task that even if divided amongst us, could consume nearly four hours. Other times, we rely on the nurses to keep us informed of “problems”. The hospital is blessed to have the services of one of the dozen native Congolese MD anesthesia/critical care intensivists in the country, Dr. Richard. He spends considerable time bedside on the wards, especially the ICU and Neonatology. The surgical team is also responsible for the Maternity service at times when our solitary obstetrician/gynecologist is unavailable. Our patients occupy half the beds in ICU as well. Any available surgeon responds several times daily to requests for consultations on the Medicine and Pediatric services. Another five to fifteen surgical patients are evaluated and admitted through the Salle des Urgences (ER) throughout the day.

Complicated malaria accounts for over 40% of non-surgical admissions. Presumed, as we lack the ability to perform diagnostic testing, typhoid is common. Many children are treated for acute complications of malnutrition, severe respiratory processes and cases of profound diarrhea, including cholera. The DRC is ground zero for Ebola and other viral hemorrhagic nightmares. Always in the back of your conscious mind is the awareness that the next patient you’re being called to see in the ER might be harboring the index case of a novel emerging infectious disease. The high incidence of gunshot wounds and higher prevalence of intestinal parasitic infestation afforded me several opportunities to note free intra-abdominal Ascaris worms during emergent laparotomies for gunshot wounds.

The compound is the basic building block of real estate for enterprise and residence in Africa. Large multi-story buildings in rural areas are rare and pose a safety risk. Security issues necessitate guards, fortified entrances and high walls topped with garlands of concertina wire or colorful shards of broken glass. Inside the walls, spaces for office work, storage, vehicles, eating and sleeping are fashioned from whatever collection of small buildings and structures that exist. All of the aid rendering Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) have their individual compounds, usually one residential and another for office functions. Local property owners benefit from catastrophe as these predominantly Western agencies drive up the area’s rental rates significantly. The city of Goma has at least 65 NGOs currently operating. The constant flow of their decaled Land Cruisers along the city’s pitiful “roads” creates real traffic jams. Even in this provincial capital there are few private automobiles. It’s large trucks and NGO vehicles sharing the roads with pedestrians, bicycles and motorcycles.

If cars are out of the price range of the overwhelming majority of individuals, small motorcycles are not. A shiny 125cc moto, most often of Chinese origin and costing about $1500 USD, is a preeminent status symbol. They also serve as the taxi fleet for local, short-haul transport. Carrying up to four individuals or large loads, the motos buzz furiously about like swarms of aroused hornets. Common sense and most organizations’ security protocols keep expatriates off these vehicles. Also, a close look at many of the drivers may give one pause. Behind those wrap-around sunglasses and trendy outfits lurk some of the toughest and meanest looking dudes in the region.

One of the solutions to the mammoth task of finding less sociopathic lines of employment for out of work rebel soldiers in nearby Ituri province, a process termed “demobilization”, was for the government to provide them a moto and taxi license in exchange for their weapon, universally a worn counterfeit Kalashnikov AK-47 with several duct tape patches. Two years ago while working with MSF-Suisse at Bon Marche Hospital in Bunia I had daily interactions with these lads as our compound adjoined one of their favorite haunts. During the day, they would taunt the passing uniformed school girls, glance menacingly at the security patrols of MONUC’s Moroccan soldiers and every now and then, give a high speed, high risk ride to a passenger’s destination. However at night they would morph back into rebels/guerillas to torment the local population and, not infrequently, die in brief firefights with MONUC forces. In African style conflict, the national forces are visible only in daylight hours; the rebels do their work at night. Both sides seem to begin drinking by early afternoon.

The MSF residential cum administrative compound is sited in Kiwanja some six kilometers from Rutshuru Hospital. A single driveway in regrettable condition accesses the hospital grounds. Picture 100 meters of an often-flowing creek bed joining the sole north- south oriented unpaved “road” from Goma. HGR-R’s solitary entrance could thus be easily barricaded by several rifle wielding militaires. Kiwanja, a ten-minute drive north, is located at a crossroads and offers several choices of overland escape routes into nearby Uganda. All the NGOs working locally are therefore based in Kiwanja proper: Solidarite, ICRC (International Red Cross), Save the Children, even the UNHCR (UN High Commission for Refugees). A large IDP (Internally Displaced Persons) camp is located at the southern end of town as is the compound for India Battalion XV; MONUC’s locally garrisoned soldiers.

Several dozen folks live in our compound; another twenty or so work here. Five drivers, four guards, three cooks, three maids (femmes de ménage), several handymen and a bevy of office staff arrive shortly after dawn and leave before dark. A dozen expatriates and eight Congolese delocalise medical professionals reside in a series of small wooden shacks adjoining a large concrete building with a central al fresco eating area. Outhouses are perched on concrete slabs containing pit latrines. Showers are taken on similar enclosed concrete slabs with buckets of hot water heated over near-constant charcoal fires. Another bunker-like building houses three administrative offices. It reminded me of a run-down but pleasant rural summer camp. The residents are well looked after: three hot meals daily, clean, pressed clothes and freshly made beds with neatly wrapped mosquito nets. Our guards are always ready to discuss the latest soccer scores or local gossip while working to make our lives safer.

I thought it curious that even our under garments are meticulously ironed until I learned that the heat of the iron killed the larvae of flies and other nasties that laid their eggs in the crevices of wet laundry hung outdoors to dry in the tropical sun. The cooks toil long hours to procure and prepare tilapia, catfish, beef and chicken dishes supplemented with pureed spinach, avocados or tomato salads. It is a fertile region; most food is of local origin. Potatoes and eggplant are often served.

Most meals offered huge mounds of a drab, clay-like substance avoided by the expatriates but savored by the Congolese: their beloved fufu. Cassava, the national foodstuff of the DRC, is remarkably easy to grow yet devoid of significant nutritional value. Yet it is the default choice of most subsistence farmers in the country because of the Congo’s shocking security situation. Raids by the troops of the warring factions require the villagers to make frequent flights into the bush leaving the crops unattended for lengthy periods of time. Often farm fields are torched to “send a message”. If families wish to eat, cassava is their sole reliable option. My take after braving several small bites: not repugnant but very bland and starchy. The taste seemed quite similar to the breadfruit of Oceania.

My first day on site featured a tour of the compound by our administrator, Gillian. I was tested in UHF and VHF radio operation, given a sheaf of background papers to review and briefed extensively on security protocols. I learned how and when we could leave the compound, of security conditions yellow, orange and red and the like. We were short on bedrooms. By convention, those staying the shortest time on site were forced to room together. This “short-timer” status is claimed in nearly every mission by the surgeons. I discovered I would be having a roommate. I then met Muthu, sprawled across a single bed in his skivvies trying to get some pre-lunch sleep after a long night of call as Gillian showed me our room. He leapt up to greet me and assist my “unpacking” which took less than ten minutes as you never really empty your bags. Within the hour, we were eating lunch with the rest of the equipe, then urgently bound for the hospital having missed dessert for what would prove to be not the only time this week.

A major joy of working with MSF is the sheer internationality of the organization. Our logistician was from Cambodia, our gynecologist from Syria, one surgeon hailed from India, another from Ireland. Our physical therapist, Vivienne, was Swiss; the mid-wife (I’ll always prefer the French term: sage femme) from France, and the nurse manager from Quebec. Dr Badri, a surgeon from the Republic of Georgia, would replace me in a month. Eleven nationalities were represented during my brief stay in Kiwanja. The archetypal MSF volunteer is a mid-30s professional, cosmopolitan and decidedly secular. From within, the organization is referred to as the “movement”. Clearly more than a job, it’s a life path, lifestyle and adventure to boot. The cadre of young “officers” encountered is impressive: eclectic experiences, a tolerance for hefty responsibilities and earnest idealism abound. Accepting a field assignment is both a sacrifice and a risk. A mission contract can be for up to 12 months; the settings, remote and conflict ridden; creature comforts, many steps below baseline. Primarily the domain of a younger crowd, plenty of the aged don’t mind the pace. Having run out of energy and ideas at three a.m. during a difficult appendectomy in Bouake, Cote d’Ivoire in 2004, I requested help from the other expatriate surgeon. Dr Odette, then 75, arrived moments later to bail me out of a potential misadventure. In Burundi in 2005, I’d encountered Marie-Catherine a graying expatriate laboratory technician and retired medical entrepreneur from Paris. She’d left her poodles and a husband thirty years her junior behind to set up a series of medical labs across the country while effortlessly maintaining an exceptional level of sartorial splendor.

Most of the surgeons in the field are 50+ years of age and contemplating retirement; the medical doctors, in their early 30s. However, fifty percent of assignments with MSF are non-medical. Doctors will often grumble that they’re under-appreciated within the organization. Once in the field the sulking medicine man soon comprehends the massive infrastructure required to get the health care providers on site appropriately equipped with uninterrupted access to labor, supplies, water and electricity. There can be no effective mission without the resourceful logistician, the “culturally aware” personnel manager and the wizardly water/sanitation engineer. No water, no hospital.

The surgical case of the day on my second day was an elective diverting colostomy. The patient was a malnourished 12 y/o girl weighing 30 kilograms. The child had a large perianal ulcer enlarging daily despite aggressive intravenous antibiotics and wound care. As the child also clearly had a grave underlying systemic ailment, we surgeons were reluctant to operate. Yet the surgery proceeded smoothly once mandated by the medical director of the hospital. The wound healed rapidly thanks to diversion of the fecal stream and the child returned home a week later.

The following day was my first “full” workday as it included night emergency call. Call was “in house”; no leaving the hospital for anything. Removed from the comforts of the residential compound, the troika of a medical doctor, anesthetist and surgeon would deal with emergencies of the night until relief appeared at eight the morning to follow. The routine would repeat every third night, more frequently if a team member was ill or on holiday.

Our mornings are spent performing complex dressing changes and wound debridements. Burns, gunshot wounds and compound fractures require operative intervention every second or third day so the daily program includes 10-20 such cases. Our protocol for most compound (open) fractures was placement of an external fixator (ex-fix).

That first “full” day began with eight pansements (dressing changes). Back-to-back emergency caesarian sections derailed further progress with the “elective” program. The last case of the morning involved an extensive adjustment of a poorly aligned “ex-fix”. Lunch was missed due to a laparotomy for a malrotation of the small intestine causing intestinal gangrene.

Rest, refreshment and relaxation back at the compound for several hours in the mid-afternoon followed before my return to HGR-R at five pm for “the duty”. The abrupt tropical night was falling as we drained a liter of pus from a breast abscess. Our next case was evacuation of retained placental fragments causing a brisk post-partum hemorrhage. I was just discovering my night quarters when another call came from the S.U. An elderly man, mostly blind owing to large bilateral cataracts, had been victimized by an unpaid soldier. After robbing the man for all he was worth, the soldier then attempted to hack off his right ear with a machete. I spent ninety painstaking minutes attempting to reassemble the mutilated fragments and control bleeding from an adjacent neck gash.

No emergencies arrived after midnight but my sleep was fitful at best. My duty room was separated from the burn unit by only several feet and a thin wall. Leonie, a three year old with 35% body surface area burns, cried plaintively and loudly most of the night.

It had taken a few days but by now I remembered why I so enjoyed these surgical missions with MSF. Unadulterated by the tiresome business aspects, the third-party payer polemic and the myriad layers of paperwork and dictations, this is “pure” surgery! Time is spent solving surgical, not administrative, puzzles. It is exhausting but exhilarating work.

Friday mornings the bloc operatoire is given a top to bottom disinfection and cleaning. Empty stocks are repleted and laundry chores completed. During these three hours the surgical team made our “grand rounds” of the services. The medical director (medecin referent) of the hospital took pity on me and accompanied us on my first such grande visite.

Wilfred was the medicin referent for HGR-R. He reported to a token counterpart from the Congolese MOH but he was top dog and called the shots. Nearing the end of his six-month tour, obviously fatigued and suffering from the stress of too many tough decisions made, Willi patiently regarded each wound, listened to every disjointed patient presentation and shrugged off my pathetic French and ignorance of the myriad of cultural subtleties. We’d worked together for a month in Cote d’Ivoire four years previously and reconnected in NYC in last year at a MSF function. This bond of shared work (and partying) within the “movement“ across several countries, even continents, fostered strength to survive the trials of Rutshuru.

MSF is committed to altering the tired paradigm of 20th century humanitarian aid: the benevolent and wise Western worker bestowing his guilt-ridden charity work on the hapless, deserving natives. Promising national staff within the movement are identified then carefully nurtured and given roles of increasing responsibility. Technical and language training is awarded those who continue to shine and ultimately these talented national staff graduate to become international staff. They continue the process by providing care in other neglected regions of the globe. My concerns about MSF creating a brain drain in these resource-starved areas had been assuaged when I’d first learned of the process of delocalisation. Here the once national staffer, now international worker returns to his country of origin to serve in a high level capacity typically in an underserved region. My colleague Willi was the perfect example. MSF initially provided him a contract to work with a small project near his home outside Kinshasa shortly after he completed medical school. He had excelled and been given further training in surgery and public health, then after six years placed among the pool of the group’s international staff. Yet Willi was imbued with sufficient commitment to and belief in his native DRC to return and work in this remote region far from friends and family at significant financial consequence. In enabling talented professionals to develop sufficient skills globally and then to provide the local framework for their utilization, MSF’s policy could one day serve as an “exit strategy” from the seemingly endless cycle of aid.

Turnover in personnel is frequent with such a large mission and as my first weekend approached I was buoyed by several upcoming social events. Forays out of the compound and hospital were special events as extra-mural activities were sharply proscribed. No expat could leave the compound alone; security rules necessitated the buddy system. Walking was permitted only along the main drag with a range of a kilometer to the south and fifty meters to the north; no side streets allowed. Visits to nightclubs weren’t condoned since soldiers predominated as patrons, putting the females at great risk. Shops could be visited briefly. Three restaurants and the town’s lone cyber café were the sole options after dark, and only until 9 pm. All four locations were less than 200 meters from the compound.

A dinner fete was on tap for Sunday evening: a going away party for Maire, an Irish surgeon completing her two month tour and Claudine, an MSF lifer heading back to France after six months serving as the Quartermaster of the Pharmacy.

The town’s one cyber café was sited near the regional office of ICCN, the Congolese version of the National Park Service, implicated via its provincial director, Honore Mashagiro, in the illegal charcoal trade and execution of ten mountain gorillas. The café’s Internet connection was of “medium bandwidth” speed and received electricity in a surprisingly sustained manner, interrupted sporadically by a short-lived afternoon thunderstorm. Most expats relished the chance to check on their emails a few times weekly. We were discouraged from tying up the virus plagued MSF office computers and the short walk was savored as a rare moment away from compound or hospital.

A stroll through town is a social experience. Children with rare exceptions initiated an interaction often just wanting to touch skin, exchange a jambo or bon jour or throw out a few words of English. Not many “donnez-moi” (give me….) requests. The adolescent toughs either avoided your eyes or engaged in playful heckling. Women of childbearing age, always occupied with large loads on their heads and infants secured snugly via cloth wraps to their backs, could rarely be engaged. Middle aged and elderly folks tended to welcome and address you formally. Most everyone was wary of being photographed. If willing, they usually asked for a small donation. After dark, when bad things happen, eye contact is rare.

The first glimpse of the magnificent “tchukudu” delights all. These ingenious conveyors of product, instruments of thrill-seeking behavior and occasional inflictors of life-altering musculo-skeletal trauma look like a cross between a huge wooden scooter and bicycle. They are unique to the Eastern Congo owing less to relative levels of motorization than their poor safety record which has them banned in less desperate countries. Not seen plying the nearby roads of Rwanda and Uganda, they are ubiquitous in the Kivu provinces of the DRC. Capable of hauling several hundred kilos or up to five small and intrepid riders, the tchukudu initially appears to be made entirely of wood and deceptively simple. I was amazed the wooden wheels and axles could handle the speeds attained on steep descents down the wickedly rutted roads. A closer look reveals the wheels have a thin wrap of salvaged tire rubber meeting the road and the axles, sanded to a near-frictionless state, are then lubricated with viscous grease. A similar technique gives the units a resilient front suspension. The riders cluster about several local shops specializing in tchukudu repair surrounded by the reclining wooden hulks in a manner not unlike that seen outside North American motorcycle haunts. Other operators stand together near markets available for hire. Snapping a stealthy photograph of several of the wooden steeds in Kiwanja, I was instantly accosted for a “contribution”. Sensing some flexibility in the voices., I hurried on to catch my walking mates passing on the chance to contribute to the local cash flow.

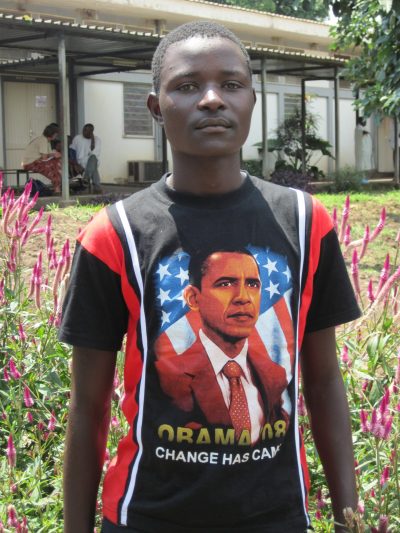

The day the Nobel Peace Prize winner was announced, I saw a stoned teenager sporting a t-shirt emblazoned with President Obama’s image in a color pattern suitable for velvet paintings. Such t-shirts were common and marijuana a popular mood enhancer. I asked permission for a photo but was publically rebuffed. Several meters and moments later, the same lad reappeared willing to negotiate a price. I compromised all ethics as we settled on the price of a quart of Primus (Congolese beer) and I snapped a quick shot. Several days later in the same area, the local police, bedecked in their crisp yellow shirt and blue trouser uniforms, staged a huge and, by all reports, productive drug sweep. The destiny of the confiscated contraband though remained a topic open to rampant speculation.

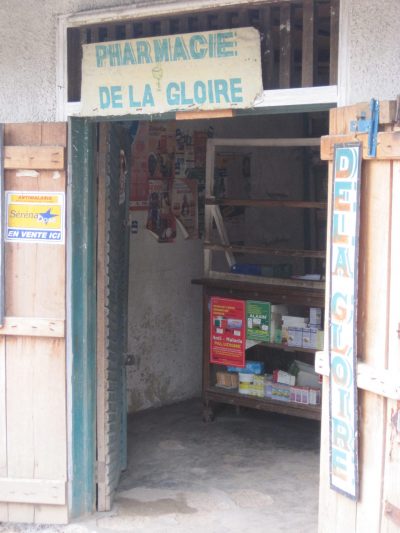

Tiny storefronts line Kiwanja’s main street. One enters dimly lit spaces inhabited by shopkeepers tending to several curious children more intently than the rare customer. Inventories were large, usually of pirated or counterfeit origin. Pharmacies were dusty yet well stocked with essential medicines manufactured most often in India. The soil so fertile, food seems plentiful but poverty makes the purchase of a varied diet beyond the means of many. Goats and chickens, some seeming dimly aware of their immediate fates, were bought and sold in animated transactions. Potatoes love the cool, moist climate of the area and are a huge source of calories. Bolts of the nearly psychedelic themed fabrics worn by rural women and girls throughout Africa are prominently displayed.

Hair is big business in Africa. Salons de coiffeur abound and also serve as hotbeds of social activity. Often a VCR plays inside attracting a dozen paying adults and throngs of children with limited attention spans but great enthusiasm for action scenes. Clients are lured inside when no movie is playing by huge murals on the outside walls portraying Western rappers and sports stars in hip poses. More pious establishments adopt monikers like the Jesus is Coming Salon. I noted more than one salon whose sign contained an extra “o” in salon and wondered if irony was indeed possible here. The Quel-est ton probleme? Saloon…

Later that evening ten members of our team ventured out to celebrate and sample the fare at Mama Bamba’s Restaurant. A desire for dietary fiber set the stage for a lapse in judgment as my share of the communal tray of cole slaw precipitated days of intestinal distress. But the cause might just as well have been my huge portion of the raw tomato and onion salad served at lunch. After those first five or six reckless days, I became much more fastidious with food selection. I also joined the queue for use of our single microwave at each evening meal as the food was often left out for hours before actual consumption since the cuisinieres left promptly at five p.m..

While in the field one exerts great energy maintaining personal health and striving to avoid even the most minor trauma. A single tick or mosquito bite can lay one out indefinitely. A minor abrasion or cut can evolve into a serious infection in the insidious manner seen only in the tropics. Most of us took antimalarials religiously as the ravages of the protozoan curse were everywhere apparent. Care was taken to obtain sufficient sleep; adequate hydration was a priority. British Berkefeld water filters and the steel canisters containing them were placed strategically around the compound’s common areas.

After a while a daily routine began to emerge. Arrive at the hospital after the jarring commute, change into surgical garb and begin operating. The scheduled surgeries, usually commencing with the youngest patients, proceed until an emergency presents. The two OR rooms run from 8 a.m. until 1 p.m. with rapid turnovers between cases. A lunch crew then breaks and returns at 2:30 to continue running a single OR room until 5 p.m. The “on call” team takes a late lunch and has a few free afternoon hours until 5 when they return for a night in the hospital. After a call night, surgeons have a free morning and night the following day but work the afternoon shift that day. Time between cases is used for consultations, making rounds on post-operative patients or simply to catch a few minutes of repose. On the surgeon’s home turf, such a routine would never be acceptable, especially in the long term. Here in a conflict zone with nearly all activities prohibitively hazardous, such a lifestyle seems more tolerable. I sensed a monastic mindset taking hold, beating back the urges for physical activity and other forms of stimulation. Knowing that a mountain bike ride is out of the question owing to land mines or kidnapping potential makes focusing on the next abscess decidedly easier.

One of our satellite health centers, located high in the mountains and in rebel held territory, sent down a young woman who had a terribly difficult first childbirth the previous day. A situation of obstructed labor had precipitated a uterine rupture. A caesarian section under primitive conditions followed. Unable to control the bleeding, the doctor, quite appropriately, had packed the pelvis with sponges and closed the incision. The baby did not survive. Transport was perilous at night so the patient was stabilized overnight and then endured the five hour ride to Rutshuru in daylight. I saw her in the Emergency Room (S.U.) in the early afternoon. She was receiving intravenous fluids, antibiotics and blood. Her condition was stable but a trip to the operating was necessary to assess the internal damage.

Within the hour, she was on the table, anesthetized and her incision re-opened. With immense relief I noted little fresh bleeding as I carefully removed each packing sponge. We revised the previous day’s uterine repair and were starting to feel pretty optimistic about the end result. Further examination prompted by the sight of urine welling up in the pelvis led to the discovery of a huge tear of her bladder. Forty-five minutes were then spent performing our best two-layer watertight repair.

On call that evening, I performed an emergency c-section on a profoundly retarded 17 year old girl. A review of her chart indicated that she was a VVS patient (Victime de Violence Sexuelle). Rape is too mild a term to describe the typical assault. Most victims report at least three attackers. Many have been violated on other occasions. Torture, robbery and mutilation are not uncommon compounders of the misery. My patient was unable to grasp the significance of her pregnancy and imminent motherhood. Her situation was scarcely unusual.

Our surgical team had two other “gifts” from the maternity ward that evening. Both were cases of post-partum hemorrhage. The first was managed routinely. The uterine muscle will not contract and stop bleeding until the cavity is empty. By suction or curettage, the offending blood clots or placental remnants must be removed. The internal lining of the uterus yields a distinct tactile sensation when the cavity is finally emptied; the massive muscle contracts forcefully and can be palpated with ease. With the second case, the bleeding continued despite removal of abundant placental material and proper tactile feedback. The hour was late and the two Congolese surgical nurses were anxious to bed down in the recovery room for the night. They began peering over my shoulder wondering what could be taking me so long. Their explanations and suggestions delivered in French just weren’t connecting in my brain. Sweating intensely I paused my efforts long enough to hear the words: “tear” and “cervix”. At the same time, noting that the remaining flow of blood was indeed much redder than that from within the uterine cavity, I finally visualized two huge lacerations of the cervix. With some adjustments in the lighting and improved exposure and retraction, I was able to rapidly repair the tears. Hemostasis was achieved; the African nurses once again having guided an expatriate surgeon in the saving of a young life.

It was probably an hour after hitting the mattress that the polite knock on the call-room door stirred me to a semi-conscious state. Blessee par balle. A victim of a gunshot wound was arriving in the OR. I was about to encounter Banzi for the first of many times.

He was a muscular mid-20s male with the look of a soldier but wearing no obvious uniform. He had been shot in the left flank and the bullet had exited just above the right pelvic bone. The circumstances of the shooting were, as usual, unclear and given the frequency of such shootings and the lawlessness of the region, also irrelevant. X-rays were not available at night. Examining the patient on the operating room table, I concluded that the bullet had not entered his thoracic cavity. We then began a laparotomy opening the abdomen through a midline incision extending from the sternum to the pelvic bone. We immediately encountered 2.5 liters of blood in the abdominal cavity. The shed blood was suctioned with the hope that fresh blood wouldn’t immediately reaccumulate and obstruct visualization. Then, placing packing methodically, we attempted to identify the injuries. The solid organs typically bleed the most; I quickly checked the liver, spleen and kidneys. They appeared intact. The next step is to identify which quadrant of the abdomen is bleeding the most and explore that one. Proceeding in this stepwise manner we discovered and repaired several injuries to the mesenteric blood vessels, which supply blood to the intestines. Finally the hollow organs are addressed: the guts. The path of any bullet is unique and rarely predictable. They enter a cavity, tumble through its various recesses, ricochet off bones and generally explode out the far side. The entry wounds are typically small, even occult; the exit wounds, gaping and destructive.

The tissue suffers both a penetrating as well as a blast injury so debridement of damaged tissue is the universal basis of war surgery. Several tedious hours were spent removing this piece of Banzi’s intestine and repairing that one. The extent of damage necessitated an ileostomy. This maneuver diverts the fecal stream away from the healing colon and into a pouch attached to the abdominal wall. A final inspection of our work followed and we were closing. We managed three hours of sleep before the sounds of a dawning day drove us to action once more.

I followed Banzi’s subsequent course attentively. A high fever on the fourth night and foul drainage from the incision the following day heralded bad news. A second laparotomy was indicated and this yielded a huge abscess caused, not from the expected source of a poorly executed repair, but an intestinal perforation in an obscure location which had gone undetected at the first operation. The fecal flow had indeed been diverted but directly into the abdominal cavity. A massive fluid collection had built up over the ensuing five days. It was a missed injury; a clear surgical error. Fatigue was the culprit and the consequences grave for our patient. Despite antibiotics, pus continued to form. Further laparotomies were necessary to repeatedly wash out the abdominal and pelvic cavities. To prevent damage from elevated intra-abdominal pressure known as the abdominal compartment syndrome, the abdomen is not sutured closed but simply covered with packing and a sterile plastic sheet. At the end of my mission two weeks later, Banzi was returning to the OR every third day for an abdominal washout and dressing change.

Human bites were frequent reasons for surgical consultations in the ER. I operated on a patient with portions of his ear chomped off. Another man developed a nasty web space infection of his hand from a bite that ultimately led to a partial thumb amputation. The bacterial fauna of the human mouth is known to cause severe and aggressive soft-tissue infections. These bites were most often the result of domestic squabbles. The most impressive wound was the amputation of the distal phalanx of a finger, including bone, accomplished in a single bite by an irate, jealous spouse.

In the typical African district hospital any patient requires a “garde de malade” or personal nurse for survival. This is usually a family member, typically a parent or spouse. The nurses are simply unable to insure that all patients are fed, watered and mobilized. The situation results not from a willful neglect but rather a staffing issue. There is not sufficient manpower to deliver the necessary care. These caretakers live at the hospital with the patient.

They cluster in the cooking or laundry areas and engage in social patterns not unlike those in their native villages. They pile their neatly wrapped belongings wherever possible. They sleep in or alongside the patients’ beds if possible. One must tread carefully in the unlit corridors at night as dozens encamp on the floor. A social order exists. One father’s theft of food resulted in his son’s abrupt dismissal from the hospital. These unsung caretakers are essential for the maintenance of an acceptable morbidity and mortality rate.

Mornings following a night of call were personal highlights of the week. A very fastidious outburst of personal grooming followed by a bucket bath with five gallons of charcoal fire heated water started things off. A late breakfast of strong coffee, jam and bread was next. Then it was either a few hours of sleep or time beneath the trees in the hammock reading and luxuriating. The chatter of the bright yellow and black weaver birds in the trees overhead created a pleasant background soundtrack. The activities of our compound’s several dozen national staff employees provided welcome visual distractions from the printed page.

It’s wise to bring a large book or two for these missions, if for no other reason than the series of long air flights going and coming. Although moments of down time do present in the field and it’s great to have something to read. Careful and appropriate selection of the perfect book is important. In Ivory Coast, Kesey’s Sometimes a Great Notion fit the bill splendidly. For a mission in the torrid Afar region of eastern Ethiopia, Barry Lopez’s Arctic Dreams was a winner. For my first mission to Congo in 2007, I chose the sublime Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver. I still cherish the moments spent reading and rereading that opening “okapi” sequence. With the current mission, the choice was the massive tome, Against the Day by Thomas Pynchon. This perverse and Byzantine novel was an appropriate backdrop to the brutal rawness of quotidian existence in North Kivu. One minor character in the book, Fleetwood Vibe, describes his compulsion to revisit this very same region as seeking “the embrace of the interior”. Reading this, I better understood my own need to return again and again to the Great Lakes region of the African continent.

The Congo in particular looms as the heart of darkness on this “dark continent”. It represents the abject failure of the African promise seemingly within reach during the era of independence from colonial powers fifty years ago. Congo’s resources are unique and unparalleled. They range from the uranium used in the atomic bombs unleashed on Japan to the blood tantalum in our cell phones. Now it’s the epicenter of endlessly unfolding, generations long tribal killing between Hutu and Tutsi factions. The largest and most sustained UN peacekeeping mission to date (MONUC) is necessary to foster even the current level of marginal security and function. Long-term players in the aid game dismiss DRC’s problems as insoluble. Personally, I felt compelled to return due to outrage at the pitiful plight of women here. The crushing poverty creates a deplorable state of obstetrical care rendering pregnancy a life threatening, high-risk condition. As the genocidiares honed their craft and the country became the poster image for crimes of sexual violence never before seen, I could stay home no longer. The place represents the worst imaginable on earth and in a perverse way, I wanted to witness firsthand how bad it could get.

In contrast with contemporary hospitals of the USA, deaths were common at HGR-R. Many were due to complex pathology and the lack of sophisticated resources. I was summoned to the ICU in the wee hours of a call night to see a 2-year-old child who had fallen from a height of eight feet or so. He’d landed headfirst and earlier in the day, another of the surgeons had attempted to elevate his skull fracture and sutured a gaping scalp laceration. My assessment of his pupil reflexes and respiratory pattern suggested the increased pressure in his swollen brain tissue would soon be lethal. As we lacked the capacity to perform a decompression procedure on the skull, I suggested comfort measures and advised the nurses to prepare mother for the worst. She was sharing his ICU bed and seemed more intent on sleeping than anything else. We had to rouse her and ask her to move to the floor to continue rendering our care. She evidenced no physical or emotional contact with the child. I was reminded of my experience in the Afar region of Ethiopia. Here childhood mortality was so common that many children were not even named until they achieved five years of age. Many children’s hairstyles included a long tuft of hair intended as a handhold for the angels to assist in their transport to heaven.

Two hours later having been summoned to the same ICU bedside, I was not surprised to find the child on the verge of death. We dutifully performed resuscitation but I was quick to pronounce it over and cease our futile efforts. The mother, having long before given up any hope, showed no visible reaction as she sat implacably on the floor beside the bed.

Later that same week and again in the wee hours, I was asked to evaluate a newborn with birth anomalies. Here I encountered an infant born less than two hours previously with gastroschisis, a condition in which the abdominal wall is incompletely formed and large portions of the stomach and intestines reside outside their usual location. In developed countries, a stepwise series of surgeries is performed to restore normal anatomy. In the current context I could only recommend warming the child with blankets and lamps while covering the exposed intestines with warm, sterile gauze. Following up on the child several days later in the neonatal ward, I was informed that he’d died the same morning. A life lost scarcely twelve hours after birth for lack of prosthetic material and anesthetic expertise.

More troubling was a case from Maternity the following week. We were performing a C-section around five in the morning. As we were finishing, we learned of a case of fetal distress and the second OR room rapidly prepared for another C-section. The mother, 18 years old and in her first pregnancy, had either confused the maternity nurses or fallen through the cracks. She’d been laboring for nearly 20 hours and the situation was grave. We had the baby out in two or three minutes, but it was too late and valiant resuscitative efforts by the nurses and anesthetist failed to revive him. I noted excessive bleeding while closing the uterus and knew a coagulopathy was developing. Bleeding continued in the recovery room. Muthu returned the patient to the OR and performed a rapid hysterectomy. However, bleeding continued and the young woman was dead before noon. Many hours were spent in the subsequent weeks analyzing this case, all in the effort to troubleshoot and prevent a recurrence.

Gunfire was frequent and seemingly random. Several mornings while clutching my pillow and struggling for a few more precious moments of sleep in the call room, I’d been dimly aware of intermittent thudding sounds seemingly nearby yet outside the hospital grounds. Surprised that rock or similar work would begin near dawn, I later learned it was artillery fire. No one knew who was firing or at whom.

Intricate security plans are developed for all MSF missions in conflict zones. Condition levels ranged from Green to Red. I was informed on my first day that things were never “green” in the DRC. A designated UN security officer assembled information which was distributed daily among the MONUC units as well as the various NGOs. Briefings were held several times weekly among all interested parties. Evacuation strategies and routes were constantly reviewed. We were instructed to have our passports on our persons at all times. Fifteen kilograms of our essential personal belongings were to be kept packed at all times. Each vehicle had several days of emergency supplies and every team member had a designated seat in their assigned vehicle. We had a large security room (salle secu) that reminded me of the backyard bomb shelters of the early Cold War. The room was stocked with tins of emergency rations, candles and batteries with large steel plates covering the windows and doors.

Lounging about the compound one evening, I tried to ignore the sound of several fusillades of automatic rifle fire. Yet they hailed from just meters away; momentarily the team was urgently summoned to the salle secu. The forced laughter and bantering of our group did not completely conceal everyone’s fears. Striving for nonchalance, we listened as several hundred more rounds were fired. Then a long silence ensued. Several minutes later, we heard the unmistakable rumble of MONUC’s tanks and armored personnel carriers. We munched chocolate bars and exchanged pleasantries while soldiers of India Battalion secured the area. After several tense hours, the phone tree came to life with the news of “all clear”. It wasn’t until the following day that we learned the cause of the hubbub. A rebel militaire had tried to rob a house but had met armed resistance. A firefight ensued which led to a small battle between several factions. By the time the UN forces had arrived, all the warring parties had retreated to the forest.

There being few alternatives, intense and wide-ranging conversations served to pass the time in the compound. Often the Anglophones would cluster together for bursts of chatter in the mother tongue. During one such session our chief, the RT (responsable de terrain), the superb and utterly bilingual Guillaume, submitted himself to intense questioning over late night beers. He thrilled us with explanations of the internal machinations of MSF and its current intramural power struggles. He gave us a plausible take on Bernard Kouchner, one of the thirteen founders of MSF and the current French foreign minister. Team members shared reminiscences of Jean-Herve Bradol, another founder and MSF major player. He had achieved respect and allure having remained in Kigali, Rwanda providing medical care during the one hundred days of genocide in 1994 at a time when all but one other Western aid organization had withdrawn. Guillaume clarified the roles of the various rebel factions in eastern Congo bringing it very close to home.

We learned that Lt. General N’Kunda’s ***** worked as a ******* nurse in our hospital. He is the renegade Tutsi commander of the FDLR currently in control of much of the Virunga National Park. His territory includes the habitat of Congo’s share of the remaining mountain gorillas. He had been “captured” by the Rwandan army as part of an agreement between Paul Kagame, the president of Rwanda and Joseph Kabila, his counterpart in the DRC. Though “The Chairman” is currently thought held under house arrest in Kigali, his forces continue to operate effectively.

Another rebel faction, the Mai-Mai, was known to have a large compound in a seemingly abandoned building thirty meters distant from ours in Kiwanja. These young men see themselves as patriotic warriors defending their home turf against the other armed factions. Their belief in magic, water purification and immunity to bullets suggests similarities to the Lord’s Resistance Army of Uganda. They have achieved a near mythic status and well-deserved fear among the local population.

Our RT also explained the subtle and intricate factors involved in the hiring of our compound and hospital personnel. Key to MSF’s success is an adherence to a policy of strict neutrality. All involved parties must be represented and receive a piece of the pie. This applies especially to employment as the high levels of salaries and the regularity of a steady paycheck elevate the employee to breadwinner and head of clan status. Our pool of drivers included individuals from all factions of the region’s conflict. Were they not united in the shared work of the hospital, many of the staff would be likely be engaged in atrocities against fellow employees. Interviewees for positions were thus evaluated not only for their skills and references but also their tribal and political affiliations.

Being the only medical game around provides an element of security as well. High-ranking officers of several factions had been treated, for the most part anonymously, in our facility. One such officer had been taken to the OR and placed under anesthesia to protect him from his pursuers, who were told his condition was critical and that he would likely not survive the (sham) intervention. We heard the story of a band of local Mai-Mai whom abruptly and for no clear reason had decided to shell the hospital. Upon learning that HGR-R represented their sole option for medical treatment if injured, they relented. Evidently, they were hedging bets on their espoused immunity to bullets.

Being a known high wage earner in an area gripped by unrelenting poverty had its risks as well. Several weeks before my arrival, one of our surgery nurses had been killed during a robbery. One night on call I evaluated one of our maternity nurses who’d been assaulted in a field near his home. He sustained a gunshot wound to the abdomen. A trip to the operating room and a wound exploration with debridement were required but fortunately the injury proved superficial and not life threatening.

A topic of frequent speculation was if the militaires were simply poor marksmen or whether they intentionally maimed, rather than killed, their victims. At one point we had five patients hospitalized with essentially the same injury: a bullet wound to the anterior shoulder. It was a survivable injury but necessitated weeks, if not months, of hospitalization and multiple surgeries. In the end, the joint would be ruined and the arm left essentially useless. In this manner a potential combatant was rendered unfit for service being unable to fire a rifle. Another preferred site for gunshot wounds was the knee joint. After enduring the requisite surgeries and a prolonged hospitalization the patient would be discharged home with a stiff, non-bending leg and a dropped foot.

Ever curious concerning the mix of players in the region, I scanned every compound and vehicle in Kiwanja (there aren’t so many) intending to learn who and what they represented. In the daylight hours, there was plenty of traffic on the road but most was pedestrian followed in frequency by bicycles and finally the occasional motorized vehicle. The bicycles seemingly without exception were nifty one speed numbers manufactured in India reliably transporting massive loads of human and commercial cargo. The vehicles were typically large commercial trucks or the SUVs of the sort favored by the NGOs. The Toyota Land Cruiser is the go-to transport for MSF and many other aid groups globally. Large decals and flags adorn each one resulting in a multi-colored alphabet soup of rolling billboards. The large trucks were a mixture of Volvo, Mercedes and Chinese brands. UN military vehicles of various shapes and sizes including armored troop carriers, jeeps and tanks thundered by several times daily in caravans leaving dense contrails of dust. Each of the white MONUC vehicles displayed the letters: UN in blue two-foot block letters. The occasional farm tractor plied the roadway. Invariably polished to an atypically bright shine, sporting the Deere logo and rarely carrying much of a load, they seemed more ornamental than functional perhaps to demonstrate the appearance of aid however ineffectual. Automobiles were rare and mostly of Japanese origin. I pondered the ubiquitous product placement the West engages in and how the Congolese might perceive it. It took me much longer to notice signs of the region’s newest big player.

During my biweekly forays into town I’d learned that most of the manufactured wares displayed in Kiwanja’s dusty shops were of Chinese origin. One day I realized that many of the trucks had Chinese lettering stenciled on their white painted exteriors. I then recalled an awful stretch of “road” we’d traveled outside Bunia in 2007 which I recently learned had been rebuilt and resurfaced by the Chinese last year. One afternoon I noticed an orderly line of Congolese adolescents patiently waiting to enter the courtyard of a compound near ours. What’s that? I’d demanded of Dr. Richard, the anesthesiologist from Kinshasa. It’s the Chinese school was his reply, ils sont partout….partout (they’re everywhere…everywhere). That same week another aid worker passed through our compound with a French language book entitled: Les Chinois en Afrique with a cover photograph showing a Chinese businessman in a suit and tie being shaded from the scorching midday sun by two bare chested Africans delicately holding parasols. The image was a modern day version of a drawing I’d seen of Henry Morton Stanley in the Dark Continent at the debut of the Scramble for Africa in the late nineteenth century. Throughout the rest of my stay I ruminated on these signs wondering how thoroughly the cultural landscape might be altered twenty years hence.

The UN story in Congo is instructive. The fledgling organization’s first peacekeeping mission was in the Belgian Congo at its time of independence in 1960. That four-year mission is now dismissed by all as an utter fiasco. The UN secretary-general at the time, Dag Hammarskjold, died in a mysterious plane crash in DRC’s Katanga province in 1961. Now MONUC, the largest deployment of blue helmets in the world, nearly 20,000, has been here more than ten years. Will they be here in another ten? Will the same NGOs be doing their thing? Or will novel agencies from China and India dominate the humanitarian playing field? Will the UN ever be able to turn peacekeeping over to the African Union and pack up? Will the tens of millions of wonderful Congolese people ever get the leaders and government they’ve deserved for so long?

I also spent many moments pondering the miserable plight of being born female in eastern Congo in these times. Culturally it’s a male dominated society. Women bear and raise the children yet also perform the bulk of the labors of daily life. Seeing elderly women toting huge loads of potatoes or unwieldy branches on stooped backs with lighter loads born elegantly on their heads was commonplace. Pre-pubescent girls hauled similar burdens in addition to a younger sibling strapped to their chests or straddling the waist. The two sexes exist in different spheres occasionally sharing space but rarely interacting. Every trip to the water pumps or to tend a field represents not just backbreaking work but also the possibility of a horrendous assault. Yet, the women smiled warmly, sung and chattered among themselves. That they accepted their lot with such dignity and grace was a source of constant amazement for me.

Late one night I was allowed a brief but profound glimpse of this feminine power. I was nearing the end of my stint in Rutshuru and mentoring my replacement, Jan, a young surgeon from the Czech Republic. I was watching him perform a C-section on a “grand multip”: a mother with eight previous pregnancies and several deliveries via caesarian. We had a strict policy that if the woman had undergone a caesarian previously; all subsequent deliveries would also be via caesarian. This policy is designed to avoid the catastrophic consequences of a uterine rupture. However the Congolese women are rarely sure of their due dates and with the consequences of delivering prematurely in our primitive setting life-threatening for the infant, we’d adopted a protocol in which all mothers would be forced to go into labor before their pre-determined surgical delivery. These C-sections were unlike those performed for fetal distress. We could proceed slowly and deliberately avoiding the rush and frenzy of a “true” obstetrical emergency.

For the surgeons, these cases are relatively calm and pleasant providing an excellent opportunity to evaluate and criticize technique. I was spending the forty or so minutes of the procedure at the head of the bed with the anesthetist sitting nearby, her work done for the moment. I began gently massaging the shoulder, then the temples of our patient. Unused to any sort of therapeutic touch, the mother looked deeply and gratefully into my eyes. I held her gaze for moments but was compelled to look away as I feared I might fall directly into her soul. The process repeated every few minutes. The spinal anesthetic had been well placed but did not completely eliminate the intense pain. I would attempt to ease some of the suffering with well-timed massage strokes. As the uterus was opened and the wrestling to free the baby ensued, our eyes locked. For several moments I was able to glimpse a bottomless dimension replete with the wisdom of generations of the feminine and all it represents in this harsh region of the planet. I knew instantly I’d seen what I’d come to the Congo to experience: this ultimate life force so much the more powerful given its origin in the “worst of the worst” scenarios.

Judith provided me a further glimpse into the suffering of Congolese women. She had arrived to the S.U. in septic shock, one of the many victims of a non-sterile and poor quality village abortion I’d encountered during my short mission. At laparotomy, the size of the uterine perforation and degree of infection necessitated a hysterectomy. Despite aggressive antibiotics, she developed recurrent pelvic abscesses requiring frequent laparotomies for drainage. She (along with Banzi) was enduring several trips weekly to the OR and her abdomen was “closed” with an empty IV bag to lessen the risk of abdominal compartment syndrome. Her status remained critical at the time I left Rutshuru.

Most women in the DRC endure eight to ten pregnancies, occasionally thirteen or more. Just prior to their C-sections while stark naked in a room of strange men and unable to move their legs as the spinal anesthetic set up, many mothers would beg me (through an interpreter) to perform a tubal ligation at the same time. Birth control and even family planning services are simply not available. As it is an intensely patriarchal society, males view their wife’s (often wives’) primary role as the bearing of children. Often unable to feed or clothe the child, the father sees each birth as manifestation of his power in the world. The operative permit for sterilization requires the husband’s consent and signature. With neither of my two missions to the DRC did a husband ever consent to a tubal ligation although dozens of women pleaded with me to perform one. I’d often thought of doing one anyway; however the predominantly male OR staff would never allow such a thing and the consequences for me would be severe. I was informed that my visa would likely be revoked and that even MSF’s mission could be jeopardized.

Just about the time I’d hit my stride with French comprehension at a peak, health stable, energy and enthusiasm intact, our administrator initiated the planning for my return home. I was nearing my end of mission. While relieved to be soon returning to a comfortable North American life, I was sad to be leaving Africa’s interior. As always, the pulse of a primordial existence, the inter-connectedness with fertile soil and the sheer humanity of the Great Lakes region had won over my spirit. I sensed the urge to return would win out once more over saner and less hazardous pursuits.

I savored my final visits with patients, the last call night and finally was adding my name and email address to the designated wall in the OR suite. Another ragged piece of paper was taped to the pale blue tiles alongside the half dozen already posted. Names, addresses and thank-you messages I’d regarded all these four weeks. Many times I’d visualized posting mine in anticipation of the journey home never thinking that the time might arrive so abruptly and with such mixed emotions.

Turnover of personnel is constant with such a large team. Having counseled and cajoled newly arrived surgeons Jan and Badri over the previous week, I found the tableau suddenly reversed. This sultry Monday morning in October I was myself awaiting transport to Goma. Over the four previous weeks I’d made no journey other than the six-kilometer trek between Kiwanja and HGR-R. Now I was girding my loins for the twelve thousand kilometer voyage across nine time zones to North America’s west coast.

Every MSF mission is concluded with a series of debriefings. While the sequential briefings at the front end of the mission prepare the volunteer for what is to come, debriefings are intended to allow for constructive criticism and evaluation of the mission and MSF itself. While there is a formal assessment of the volunteer’s performance, most of the time is spent brainstorming ways in which the organization might improve things on both the micro and macro levels. These debriefings occur at each stage of the journey home beginning on site and progressing to the regional (Goma), organizational (Paris, via telephone this time) and finally national (NYC) MSF office. Several hours were set aside Monday morning for a final strategic huddle with Guillaume and Willi prior to my departure from Rutshuru. In Goma on Tuesday, the process commenced at first light as logistics required an early start for the drive across the Rwandan frontier and into Kigali. Several complicated operative cases were painstakingly rehashed at my morning meeting with the MedCo (medical coordinator) Manal, a brilliant young female physician from Sudan. I recommended some adjustments in the organization of Rutshuru’s surgical team and record keeping with the hope of improving our somewhat haphazard post-operative care. By mid-morning I was enjoying my last glimpses of the Nyiragongo volcano and Goma as we sped to the border crossing.

In leaving the DRC I experienced the reverse process I’d undergone on entry: escaping the near chaos of the Congo for the relative order of Rwanda. The size and scale of this country of eight and a half million citizens in addition to its distinctive topography (mille collines) had permitted a well-intentioned government to create a model, progressive country. I could envision no similar process for the seventy plus million souls spread over the Congo’s immense and varied land mass. Fifteen years following the genocide in Rwanda, a transformation had evolved. President Kagame with his zero tolerance of corruption approach has fostered a stunning rehabilitation. Education is compulsory and well funded. Motorcycle helmets are mandatory; the law is strictly enforced. Family planning services abound and in contrast to the neighboring Congo, not every female of childbearing age is simultaneously pregnant and carrying an infant. Plastic bags are outlawed and confiscated when passengers deplane at the airport in Kigali. Children are taught to wave enthusiastically at foreigners; begging is curtailed. A truth and reconciliation process, modeled on an ancient village tribal justice process with elements of the modern South African system, is ongoing. Driving through the countryside one sees large groups of men in blue jumpsuits (former interahamwe, loosely translated as: “the guys who get it done”) constructing roads and adding terraces to the already extensively manicured hills. These are minimum security “prisoners” serving their sentences for genocidal crimes before release back to their home villages. In many cases, they must provide financial support to the widows and survivors of individuals (often neighbors) they’ve murdered. Amazingly, at least on the surface, the process seems to work. A visitor can’t help but sense a concentrated effort to forgive. To forget is not in the plan.

Rwanda’s growing tourist trade revolves around the two Gs: gorillas and genocide. I visited several genocide memorials. All feature mass graves and gardens. With a distance of only fifteen years, the visitor has little difficulty imagining the horrors that occurred literally underfoot. In Ntarama, a stairway leads to an underground crypt containing hundreds of carefully arranged skulls, many showing evidence of blunt trauma. The church in which thousands were killed over several days having been lured to false sanctuary by corrupt priests displays their rumpled clothing piled on pews. Bloodstains still mar the walls. The effect is profound and deeply disturbing. Never again is the resolute refrain posted everywhere.

Usually thought of as a French speaking country, Rwanda is aggressively trying to join the ranks of Anglophone countries. Commercially they’ve allied themselves with the East African Trade Union, which is dominated by the former English colonies of Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania. Arriving in Kigali en route to Congo a month earlier, I’d first learned of this switch on the street. I was heading to Goma in an MSF vehicle accompanied by three French expatriate volunteers. We’d stopped in town for food and fuel and were engaged in conversation by an idle moto taxi driver. When my colleagues began speaking their rapid and idiosyncratic French, the taxi man brusquely admonished them to “please speak in English”. Rwandan school kids endure daily English instruction. In restaurants in Kigali, I overheard many businessmen and officials conversing with great effort in broken English phrases. A random question in French was typically answered in English.

Rwanda’s 300 or so mountain gorillas contribute mightily to the economy. I’d plotted for months to arrange a trek as my end of mission reward. The Parc National des Volcans is Rwanda’s share of the great parkland of the Virunga Mountains. Virunga’s largest landmass lies within the borders of the DRC. I’d gazed daily at its lofty peaks near Rutshuru and I seen the park’s shabby headquarters as we passed through Rumangabo. The dense jungle as seen from the road resembled the set of a Tarzan movie shot on location. Gorilla tours in DRC were available but essentially black market activities as the territory was controlled by the FDLP. Ethical travelers were encouraged to trek elsewhere. MSF security rules strictly forbade these tours as well. Another portion of the Virunga range falls within the borders of Uganda and contains over 100 mountain gorillas. In 2007 I’d tried to obtain a trekking permit for Uganda’s Bwindi National Park but my only potential days had been sold out weeks earlier. To avoid similar disappointment, I’d arranged my Rwandan trek prior to leaving North America.

Rwanda runs a slick yet credible gorilla tourist operation. They track about fifteen “families” of the nomadic gorillas. These groups are comprised of an alpha male “silverback”, three or four “wives” and a dozen or so youngsters. Half of the families are the purview of researchers and off limits to tourists while five gorilla groups endure daily one-hour visits from gaggles of eight tourists. The trekking permits cost $500 USD and forty are sold each day, so the primates generate a steady and sizable flow of cash for the nation’s coffers. Visits are limited to one hour to avoid stressing the animals. A seven-meter distance is maintained to prevent disease spread in either direction. Two park rangers, three trackers, several porters and two soldiers toting assault rifles accompany each tourist group of eight. The trackers spend their days in the forest informing rangers of the precise locations of the animals. With machete wielding porters leading the way, my group stepped over the 76 km long rock wall separating huge potato fields from the national park. Our elevation of 2500 meters, the towering volcanoes nearby and a dense afro-montane forest canopy created a magical and unique ecosphere evoking anticipation of “gorillas in the mist”. Everyone wondered why the soldiers accompanied each group. We were told their purpose was to protect us from marauding buffalo, known throughout Africa to be dangerous and aggressive beasts.

Our trackers had done their jobs well. Within an hour we’d located Group Thirteen. They were enjoying a pause for play and foraging in a dense bamboo thicket. In spite of the huge build up and the readiness to be disappointed, each member of our group was totally mesmerized by the all too brief time spent on the jungle floor in the company of the gorillas. As we slipped and stumbled our way back to the potato fields, I overheard the comment: “truly five star”.

As testament to the sheer marvel of jet age travel and in spite of the associated travails of economy class, I was enjoying a steaming bowl of Tom Yum soup in a midtown Manhattan eatery thirty-six hours later. The embrace of the interior had been broken, if only for a brief time.

Michael Hauty

El Sargento, B.C.S., Mexico

January 2010